Blogpost

Is life2vec a mess?

What the internet got wrong

· Updated · 2927 words · 14 minute read · By Germans Savcisens

Over the past two years, online death calculators have flooded the internet. I think the craze really took off after the introduction of the life2vec,1 a model developed by a team of scientists, including myself, trained on life sequences from millions of Danish residents. Since then, life2vec has been often mentioned for its ability to predict “when you are going to die with 78% accuracy,” alongside the claims that it is powered by the same architecture as ChatGPT.

Chances are, you have stumbled across one of these calculators. They often claim to use life2vec under the hood, with names like “Life2vec AI Death Calculator.” They quite often appear at the top of the search results and even make their way into news coverage. Maybe you have even tried one. Perhaps it promised you a century of life, or informed you that your time is up tomorrow… In either case, it likely left you with questions: “How accurate is it?” “Is this really THE death calculator everyone’s talking about?” “Is this the model with the 78% accuracy?”

I have to admit: the title was a bit of a tease, and for that, I owe you an apology. Despite what these online tools claim, they have no connection to the life2vec we built in our research. Instead, this post is my attempt to clarify our findings: to explain what life2vec really is, why I believe it was a meaningful scientific project, and why it simply cannot be used online to predict anyone’s death date.

This is written for curious readers, journalists, policymakers, and scientists. You might ask why this explanation should differ from similar pieces you have seen elsewhere. My answer is simple: I was the first author of the life2vec paper, and I spent three years, alongside brilliant co-authors, bringing this project to life.

Data

Our work on life2vec aimed to enhance understanding of life trajectories, opening the way to improve public health strategies and social policies. To make this concrete, it helps to start with the data, since it is easier to put life2vec into perspective once you understand what goes into it.

Most online death calculators ask for basic details like your age or self-reported health information, such as whether you smoked in the past year. In contrast, life2vec was trained on sequences of records from national administrative registries2 covering millions of individuals. These records combine detailed medical events, such as diagnoses and hospital visits, with socio-economic data, including employment histories, residential mobility, and occupational skill profiles. Crucially, this data is time-ordered for each individual, capturing how health and social factors unfold across an entire life course rather than as isolated snapshots.

Let’s consider income records. Whenever a Danish resident receives taxable income (whether from a salary, pension, social benefits, or sick pay), it is documented as a single record in a table. Each record includes basic demographic attributes such as age, sex, and place of residence, along with the type of income received. If the income comes from employment, the record further specifies the employer’s industry3 and the individual’s job role4, both encoded in a highly structured way.

A typical record might look like this:

- Date: January 2, 2011

- Income: 32,000 DKK

- Industry: 1814

- Occupation: 7323

This record can be interpreted as follows: on January 2, 2011, an individual working as a Print Finishing and Binding Worker (occupation code 7323) at a Bookbinding Service (industry code 1814) earned 32,000 DKK.

Health records follow the same principle. In Denmark, the vast majority of doctor visits and hospital stays are also logged in a highly structured format. Each encounter is associated with one or more diagnoses encoded in the ICD-10 classification system. A doctor can pinpoint a diagnosis down to an injury/disease that occurred during “activities involving arts and handicrafts” (ICD-10 code Y93.D). Yes, the data is that precise.

By combining these two data sources, we can piece together detailed timelines of individual lives. However, there is an important catch: at the end of the day, these are still just records in a massive table… some events are rare, others repeat with various frequencies, and many classical analysis methods require us to simplify this complexity. For example, one might instead count hospital visits for a specific issue or average yearly salaries.

Such simplifications, however, come at a cost. They strip away context and temporal ordering. Having your tonsils removed in your twenties is not the same as having them removed in your forties. Returning to full-time work and then developing back pain tells a very different story from developing back pain first. When we collapse life histories into aggregates, we risk erasing these connections.

Context, Order, and Language

One of the central goals of the life2vec project was exactly to preserve the rich context and ordering of life sequences, while still enabling exploratory analysis. That is, both to uncover connections between events and, potentially, to make and interpret life-related predictions.

To approach this problem, we drew inspiration from another field that faced similar challenges: Natural Language Processing (NLP, for short). Human language, after all, consists of ordered sequences where meaning depends not just on which words appear, but when they appear and in what context.

To demonstrate this, let’s look at a small example. Suppose I tell you that the sentence contains the following words: and, beautiful, everything, hurt, nothing. Could you reconstruct the original sentence? Well, yes! You might come up with several plausible sentences:

- “Beautiful was nothing, and everything hurt.”

- “Hurt was everything and nothing was beautiful.”

- “Everything hurt and nothing was beautiful.”

All of these use the same words, yet their meanings differ a lot. The sentence I had in mind is a line from Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five: “Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt.” Did your reconstruction look anything like that? So… I hope it does show that counts alone are not enough when it comes to English language: order and context shape meaning.

For decades, NLP researchers have focused on developing methods to represent human language so that machines can process, interpret, and generate it. Around 2016, this line of work gave rise to a particularly powerful class of models: Transformers.5 These models forever changed the NLP field, and some might argue that they eventually broke it (that’s for another blog post).

Modern models such as ChatGPT or Gemma are built on the Transformer architecture, and it makes them quite powerfull. You have likely seen this for yourself: they can process quite complex information and generate coherent, human-like text. More importantly for our purposes, Transformers learn rich representations of language that encode how words are related to one another across context and position.

You do not need to understand the inner workings of Transformers for this post (here is a more technical explainers6 for interested readers). At a basic level, Transformer models convert an input sequence, such as “The dog runs after the,” into a compact numerical representation that captures its content. It does so by combining mathematical operations; the important point is not how these operations work, but that they preserve order and context while producing numerical summaries that can be used for prediction and, to a limited extent, interpretation.

This combination of strong predictive performance on structured sequences and interpretability led us to a simple but ambitious question: What if we could represent life sequences in a form similar to human-written language, and further adapt the Transformer architecture to learn this life language?

The Language to Encode Life

To apply Transformers to life-related records, we had to define some sort of language. The language we developed is super simple, and, most importantly, it bears little resemblance to human-written language. This synthetic language is intentionally simple, with only a few basic rules. Unlike human languages, it does not include grammar in the traditional sense: there are no conjugations, inflectional endings, or function words. We left these elements out because they do not add much meaning for our purposes and would only introduce additional structure for the model to learn (i.e., things that are not connected to health or labour).

Instead of words like dog or beautiful, the vocabulary consists of codes derived from the data (like INDUSTRY-1814), and we have something similar to sentences (each sentence represents a single record in the data). The vocabulary contains only of 2 000 words (way fewer than in English).

So, taking my previous example with the labour record:

- Date: January 2, 2011

- Income: 32,000 DKK

- Industry: 1814

- Occupation: 7323

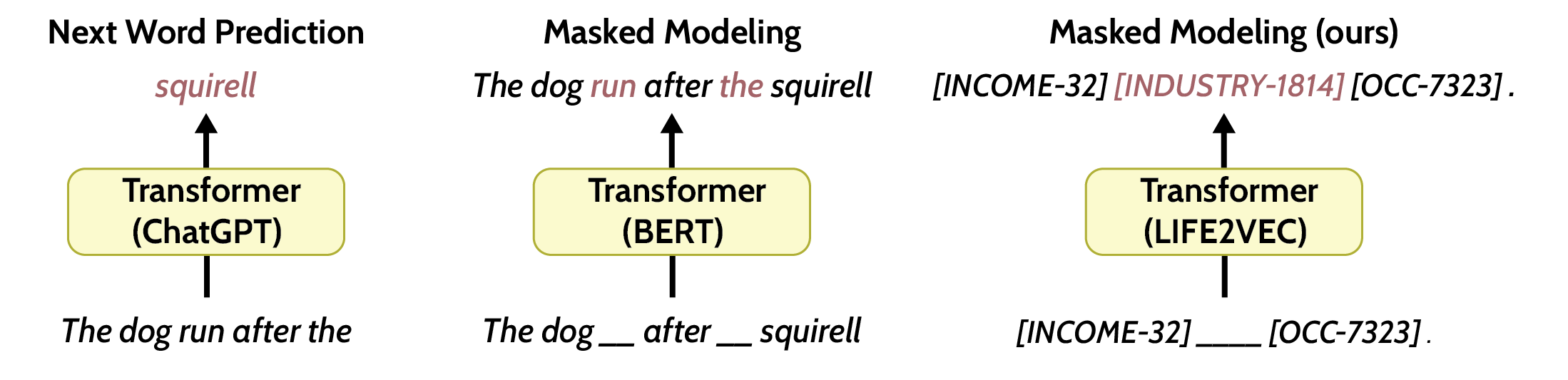

In our language, this record becomes a sentence: [INCOME-32] [INDUSTRY-1814] [OCC-7323]. An individual life trajectory is then represented as a sequence of such sentences. A person might have 12 to 100 such sentences, which eventually form a kind of book for that person.

[INCOME-32] [INDUSTRY-1814] [OCC-7323] . [AMBULANCE] [HEALTH-S60]. [INCOME-63] [INDUSTRY-1814] [OCC-7323] .

This is a slightly simplified example, since we have many more categories and code types, but you get the idea. You should also understand that, since we have used such detailed records, we cannot make the data public (the same argument goes for the life2vec model), which would constitute a huge privacy violation.

Some have proposed representing life sequences directly in English and further using pretrained models such as ChatGPT or Llama to make predictions. At first glance, it might sound like a low-hanging fruit. However, it comes with a fundamental issue: we have no idea what went into the pretraining of these models, nor the biases they may have accumulated along the way. To put it into perspective, ask yourself the following: Would you want a model trained partly on posts from r/WhatWrongWithYourDog to make predictions about your future career?

The Model to Capture It All

As should already be clear from the synthetic language, life2vec is not something you can meaningfully chat with in English. But there is another, more crucial reason why chat-like conversations are impossible: the way we trained the model.

Most modern transformer-based chat systems (again, ChatGPT as an example) are trained to predict the next token in a sequence. This makes the most sense for the task ChatGPT has to accomplish, namely generating coherent replies.

Life2vec was trained very differently. Instead of next-token predictions in a sequence, as in chat-based models, it used a masked modelling objective.7 In this setup, parts of the sequence are hidden, and the model is tasked with reconstructing the missing elements from the surrounding context. Think of it like a puzzle where certain pieces are missing. This approach helps the model understand the relationships and patterns among events in a sequence, rather than focusing solely on what might come next. After seeing thousands of sequences, life2vec gradually learned how to encode life histories into numerical representations. That distinction is crucial: our goal was not to predict “what comes next,” but to learn compact numerical representations that summarise entire life trajectories.

These representations can then be used for downstream analysis: to study how health and labour events are interconnected, to explore hidden structure in life trajectories, and to provide carefully defined prediction tasks. What they cannot do (and were never designed to do) is hold a conversation or generate a personalised life trajectory.

I will dedicate a separate blog post to explain what life2vec actually learned about this language; it did surprise us a lot. Long story short, the life2vec model learned to navigate this symbolic language and identified meaningful connections. For example, certain occupations, such as kitchen work, were indeed associated with the development of pain. Many of the patterns the model learned aligned well with established findings in labour and health research. Given that life2vec was a proof-of-concept, this was an encouraging outcome.

On Mortality

That said, this post is about death predictions, so let’s get back to that.

Now that life2vec was pretrained and learned to operate on sequences, we could use it to summarize the input. Given a complete life-sequence, Life2vec produced a numerical representation of that sequence. The question that remained: do these compressed representations of sequences carry any meaningful information?

Death prediction entered the picture not as an end goal, but as a validation task. Mortality is a well-studied phenomenon, and if life2vec could provide insights that align with our knowledge and match (or outperform) existing approaches, it would support the idea that Transformer models and textual representations of life sequences can be useful for computational social science. We settled on a simple downstream task: given a life sequence ending on December 31st, 2014, could the life2vec model identify individuals who would die within the following three years? It was a binary classification problem: no predicted dates, no fine-grained timing, a fixed prediction window ending in 2018 (A small note: during pretraining, life2vec never saw any information about events that occurred after 2014/).

Under this setup, the model performed well, outperforming several classical methods, and identified connections we know lead to higher mortality, such as working in a physically demanding position. Notably, the often-quoted figure of 78% accuracy was never emphasised in the main paper. Accuracy is not always the most informative metric, and this number appeared only in the supplementary materials, consistent with practices in our field. To be precise, what this number means is the following: if I take a group of 100 people that consists of 50 people who died within the prediction window and 50 who were still alive by the end of 2018 → life2vec would correctly classify 78 of them (on average).

To summarise the arguments above, the life2vec model cannot do the following:

- accept free-text English input

- operate as a chatbot

- predict individual death dates

- be deployed online

- generate personalised life narratives

Conclusion

Let’s return to where we started.

The online death calculators circulating today are not built with life2vec. They do not have access to the data, the representations, or the training setup of our project. They are not simplified versions of the model, nor are they rough deployments of the same ideas. They are entirely separate tools, borrowing a name and a narrative without the substance behind it. We do have a page online8 that answers additional questions on the aim, privacy, and data, but again, it is not a calculator.

Life2vec itself was never designed to predict individual death dates, and certainly not to be queried interactively online. It was a proof-of-concept: an exploration of whether rich, time-ordered life trajectories could be represented as sequences without flattening their structure, and whether Transformer-based models could learn meaningful representations from them. Death prediction was used in this work only as a validation task.

Life2vec was never about telling individuals when they will die. It was about understanding life trajectories without erasing their complexity, and about exploring how modern models might help social scientists do that better.

Afterwords

This post ended up being longer than I initially planned (and still did not cover even half of what I originally intended). If all goes well, I will dive deeper into specific aspects of the life2vec model in future posts, including a more detailed discussion of death prediction and other tasks we explored, such as self-reported personality assessment.

Why talk about this now, long after the paper came out? This year, I had the chance to travel and share the project with the public, industry leaders, and scientists. I discovered that many genuinely believe these online models are tied to our research. There’s even a Life2vec crypto coin (again, not connected to our project) claiming fuel for the Life2vec ecosystem. Clearly, it’s time to set the record straight.

The material in this blog post is based on multiple slide decks I have presented over the past years.9 Everything here reflects only my own views, not those of any institution or co-author. Finally, I used Grammarly AI and ChatGPT to look for synonyms and phrases that streamline the flow.

TL;DR: What life2vec is and isn’t

Germans Savcisens, et al. “Using sequences of life-events to predict human lives.” Nature Computational Science 4.1, published January 17, 2024, 43–56. ↩︎

Danmarks Statistik. “Statistics Denmark — Official National Statistical Authority.” ↩︎

International Labour Organization. “International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08).” ↩︎

Danmarks Statistik. “Dansk Branchekode DB07 — Danish Industry Classification.” ↩︎

Ashish Vaswani, et al. “Attention Is All You Need.” NeurIPS, 2017. ↩︎

Jay Alammar. “The Illustrated Transformer.” Blog post, published June 27, 2018. ↩︎

Jacob Devlin, et al. “BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding.” NAACL, 2019. ↩︎

Germans Savcisens and Sune Lehmann. “life2vec — Official Model and Publication Source.” Webpage, Published January 6, 2024. ↩︎

Germans Savcisens. “Life2vec: Foundation models for registry data @ Complexity Science Hub.” Zenodo record, published November 18, 2025. ↩︎